Shakespeare as Actor

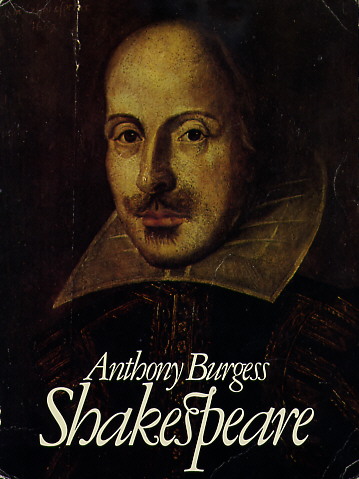

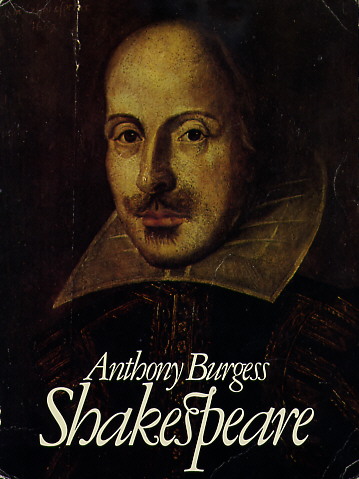

by Anthony Burgess

Shakespeare as Actorby Anthony Burgess |

|

There is also

Will Shakespeare, who is making up for the Ghost. At thirty‑seven he is grey

enough; he needs but little art on his receding hair and his beard. (...)

He has put much

of himself into his tragedy, but he did not choose to write it. Burbage came

across that old Hamlet of Tom Kyd in the play‑trunk and suggested that, since

revenge tragedy had become popular again, it might be a good plan to do

something sophisticated and modern with the old tale of the Danish prince

who feigned madness to encompass revenge of a murdered king and father. (...)

Most of the actors are mouthing their lines. (...)

Music. Trumpets.

The flag flies from the high tower. The play begins. On the tarrass or gallery

a nervous officer of the watch: there have been nervous officers enough during

the Essex troubles. All these Danes have Roman names, Italianate

anyway: the groundlings cannot conceive of a tragedy without hot Southern

blood in it. Francisco, Horatio,

Marcellus, Bernardo. It is broad daylight

and the autumn sun is warm, but words quickly paint the time of night and

the intense northern cold. Eerie talk of a ghost, Horatio sceptical in the

modern manner. Then the Ghost appears, Will Shakespeare, the creator of all

these words but himself, as yet, speaking no words. (...)

Denmark is, for

the moment, England; the audience still remembers that Christmas earthquake.

Backstage, Armin does a skilful cockcrow. The Ghost glides off. While Horatio

and the soldiers finish their scene on the tarrass, the main stage below

fills up with the court of Denmark.

Trumpets and drums

for Claudius, the boy Gertrude beside him. (...)

Now the tarrass

again, and the air biting shrewdly, a nipping and an eager air. Hamlet, censuring

the Danes for their drunkenness, is in danger of becoming dull. Good, the

attention of the groundlings is wandering, there are some coughs. Now into

that dullness the Ghost thrusts himself again, and the growing inattention

is jolted awake. The Ghost beckons Hamlet away, which means that both leave

the tarrass and take the stairway quickly,

re‑entering on the main stage below. The five lines shared by Horatio and

Marcellus are just enough to cover their passage. So this great speech of

the Ghost can be made in the main acting area. The bookholder is ready to

prompt, for Will is not always reliable, not even with the lines he has himself

written. And now the Ghost's morning dissolution: no cockcrow this time,

since an effect is diminished by repetition. The gallants from the Inns of

Court, on their stools left and right of the stage, are already writing down

odd lines on their tablets: they will quote them that evening at supper.

from Anthony Burgess,

Shakespeare (1970)